David Bharier, Head of Research, British Chambers of Commerce

Dr Laura Kudrna, Associate Professor in Health Research Methods, University of Birmingham

Sickness absence is becoming a significant burden on UK productivity and employers are under increasing pressure to respond. The first randomised controlled trial of its kind, funded by the Work and Health Unit and National Institute for Health and Care Research, tested whether direct payments could encourage small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to invest in employee health and wellbeing.[1] The results suggested that incentives helped employers introduce new health initiatives, but that these actions did not directly translate into improvements in employee health or wellbeing.

The growing economic impact of sickness

The labour market is facing increasing turbulence, with post-pandemic health problems now a key constraint on both recruitment and productivity. Rising sickness has driven the increase in the UK’s economic inactivity rate, which remains stubbornly high at 21.1%.[2]

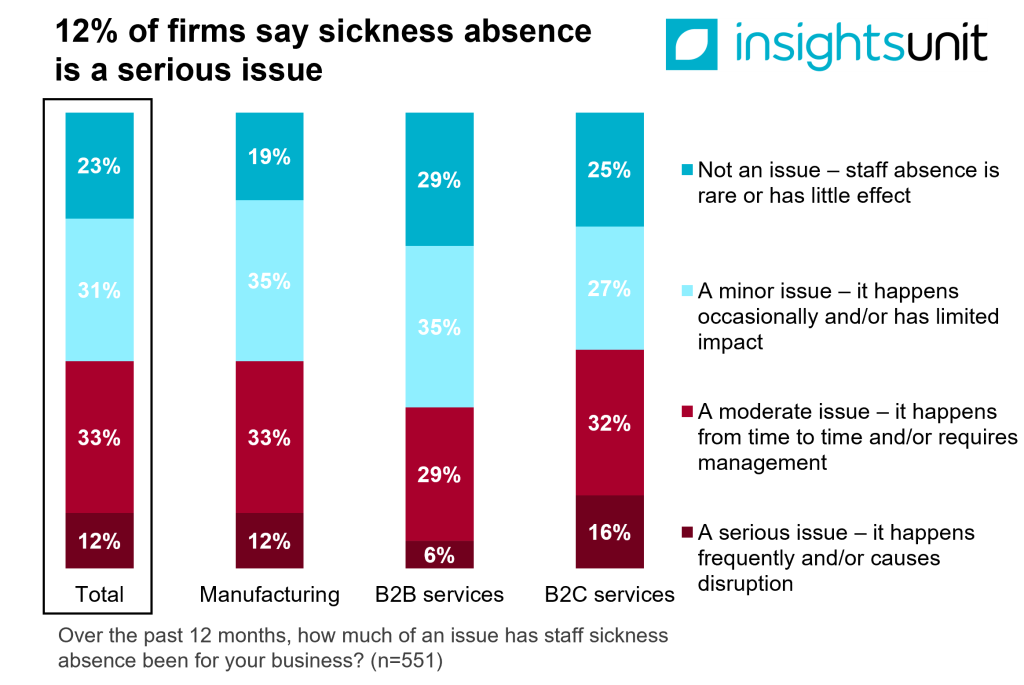

A 2025 British Chambers of Commerce (BCC) survey of 551 businesses found that 12% described staff sickness absence a serious issue, occurring frequently and causing disruption, while a further 33% reported it as a moderate issue.[3] For firms with more than 50 staff, the impact is sharper, with 17% reporting it as serious and 41% as moderate.

Meanwhile, firms are reporting skills shortages at near historic highs. The BCC’s Quarterly Economic Survey consistently finds that around three quarters of firms who attempt to recruit face difficulties doing so.[4] While increasing labour costs are cited by businesses as the biggest concern, workplace sickness is intensifying the strain.

Despite these challenges, evidence on effective interventions is limited, particularly for SMEs with less than 250 staff, which often lack the capacity to deliver structured health programmes.

Paying businesses directly

To understand what works in practice, in 2023, the Work and Health Unit, with support from the National Institute for Health and Care Research, funded a peer-reviewed randomised controlled trial with 100 SMEs across the West Midlands, each employing between 10 and 250 staff. Firms were assigned to one of four groups: a high-incentive group offered up to £10,000, a low-incentive group offered up to £5,000, and two control groups. Employers were given the flexibility to decide what to spend it on to support local priorities. Examples included lifestyle subsidies, gym memberships, health communications, new training, and occupational health providers.

Researchers then assessed outcomes at each stage of the intervention: 1) whether employees perceived employers to be acting, 2) areas of action (mental health, musculoskeletal health, lifestyle health), 3) whether employees engaged, and finally 4), whether employees reported changes in health and well-being. Data came from baseline and follow-up surveys at 11 months, alongside in-depth interviews with both employers and employees.

Employers moved but employees didn’t

The trial revealed a clear split between employer and employee behaviour. Employers that were offered the payments were far more likely to introduce initiatives like wellbeing policies, workshops, and increased communication about health support. Statistical analysis of the chance that employers took more action in response to the incentive supported this conclusion.

Staff within these firms noticed the changes. Reports by employees of improved health provision were 12 percentage points higher than in the control group. Many staff could describe new initiatives, and crucially, the effect grew with the size of the payment, showing a ‘dose-response’ effect.

However, despite these changes, there was no evidence that the employees themselves altered their health behaviours. Surveys of individual health behaviours, such as exercise and diet, and of mental well-being scores, showed no meaningful improvement. So – incentives succeeded in kickstarting employer action, but not in producing measurable improvements in employee health outcomes.

The gap between employer and employee action

Why did these employer initiatives fail to translate into individual behaviour change? The study highlights three main factors:

Organisational capacity: While incentives triggered initial action, many SMEs lacked the in-house capability to design and sustain tailored programmes. Employee interview feedback suggested that initiatives were too generic or poorly targeted to be effective.

Barriers to uptake: While awareness was strong among staff, many faced practical barriers to accessing the initiatives, such as workload pressure or lack of managerial support. Employee health needs assessments – questions about what they wanted – were provided and actioned but seemingly not memorable for employees who reported their needs were not met.

Outcomes take time: The trial ran for just under one year. Health and well-being services, like any major cultural shift within an organisation, can take several years to embed and produce results. One-off incentives in a relatively short time frame are unlikely to reshape employee behaviour.

Towards a wider set of reforms

It’s clear from the study that cash interventions alone won’t be the silver bullet. Meaningful progress depends on a broader set of reforms that make it easier and more affordable for businesses to invest in prevention, manage sickness absence effectively, and support people back into work.

The BCC’s Growth Through People: Making Health Work report, released on 25 September, sets out a range of steps needed. This includes the introduction of a voluntary Health at Work Standard, easing cost barriers through tax reform, improving sick pay and fit notes, and expanding access to rehabilitation.[5] It also calls for better access to training for SMEs, guidance on disability pay gap reporting, and wider flexible working, including menopause support. To reduce economic inactivity, the report recommends wage subsidies, more resources for Access to Work, and simpler employment support delivered through Chambers of Commerce.

Taken together, these measures would give employers the confidence and tools to embed health into workforce planning, rather than treating it as an add-on. For policymakers, the message is clear: combine financial incentives with practical reforms that reduce costs, build capacity, and simplify access to support. Only then can the UK deliver healthier staff, stronger businesses, and a more resilient economy.

Further Reading

- Trial details: PLOS Global Public Health: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0001381

- BCC report: Growth Through People: Making Health Work: https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2025/09/long-term-sickness-blighting-uk-economy/

- BCC Insights Unit publications: https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/insights-unit/publications-and-commentary/

[1] https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0001381

[2] ONS Labour market overview, UK: September 2025

[3] https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2025/09/long-term-sickness-blighting-uk-economy/

[4] https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2025/07/recruitment-static-as-firms-assess-ni-impact/

[5] https://www.britishchambers.org.uk/news/2025/09/long-term-sickness-blighting-uk-economy/